The body was at the heart of the colonial encounter. – (Mills and Sen, 2)

Among the many discourses that became prevalent as justifications for colonialism and slavery, the discourse of the inferior body and mind of the colonial subject became one of the most prominent narratives behind the grand truth of the colonial empire's advancements. The colonial bodies “were vaccinated, dissected, drugged and carefully gendered by Western medical institutions” (Mills and Sen, 2). Science and technology emerging from the global West evidently played a vital role in this, as practices such as the study of phrenology, initially considered a study of human psychology, quickly evolved into a theory of racial classification that ultimately became fundamental in the justification of colonialism and slavery, as it had “proven” the elevated mental and physical status of the “white race.” Given the centrality of the body—and what Foucault terms biopolitics—within both colonial and, consequently, post-colonial discourses, this reading of Saadat Hasan Manto’s 1950 short story Thanda Gosht attempts to focus on the figure of the colonized body: its abjection and consumption, the breakdown of corporeal boundaries, and the omnipresent spectre of the white master, forever lurking in the background of the colonial subject’s psyche.

The abject is that which disturbs the structure of the “I.” Following Kristeva’s theorization, the abject is that which must be cast aside to become an independent subject. The abject blurs the line between the “I” and the “Other”; however, what makes it truly frightening and simultaneously fascinating is that the abject is not a radical exteriority, but rather a part of ourselves that we try to distance ourselves from but can never fully escape. In the narration by Manto, it becomes evident that Ishwar Singh's acts of looting, murdering, and raping are not simply acts of mindless pleasure; they serve another function as well—namely, the solidification of Ishwar Singh as The man. He, as soon as the colonial master has left, takes on his character and starts to assert his identity as the new master of this land. In the case of Ishwar Singh, the new “Other” that has emerged is the Muslim. All characteristics of the colonial subject are now transferred onto this new Other. In order to become the stand-in for the white master, however, Ishwar Singh must first be able to mirror some of his characteristics. He is tasked not only with differentiating himself from the new “Other” that has emerged in the backdrop of Partition but also with stepping out of the shadow of his own past as the colonial body, for “the bodies of the local population were imagined to be inferior by the British, who saw them either as weak and feminized or as brutal and martial” (Mills & Sen, 2).

His transgressive actions against the people among whom Ishwar Singh had found himself at home just a few weeks ago also reveal a desperate attempt not to end up like the thousands of dead bodies stacked up at the corners of every street and road in the city. This reveals the persistent horror in the backdrop against which the whole story is narrated. Much like Manto's many other stories, such as Khol Do, Toba Tek Singh, or Tetwaal ka Kutta, the backdrop effectively encapsulates the discomfort and horror elicited from what is abject. In all of these stories, the breakdown of law and the ensuing chaos are emphasized. As Ishwar Singh narrates the story of what he experienced eight days ago, readers are left repulsed by his blatant disregard not only for institutional laws against looting and trespassing but also for universal cultural laws against murder and rape. These acts can be interpreted both as violations of another human being and, from a more patriarchal standpoint, as violations of someone’s property (from the perspective of a society that emphasizes the violation against family, particularly paternal masculine figures such as the father and brother). Such blatant disregard and transgression against what essentially solidifies our place and identity in culture and society bring about a destabilizing effect on the parameters that construct the very core of our symbolic identities—putting both the characters in these stories and the readers into a state of cognitive dissonance. As Kristeva notes, “Any crime, because it draws attention to the fragility of the law, is abject, but premeditated crime, cunning murder, hypocritical revenge are even more so because they heighten the display of such fragility” (4).

The collapse of meaning, however, is not limited to the setting in which the story is situated. Manto draws on the breakdown of another boundary—a highly gendered one—between activity and passivity, which also functions as an interconnected representative of other binaries: masculinity and femininity, exploration and rigidity, colonizer and colonized, living and dead, and, lastly, hot and cold, as reflected in the title of the story itself. All of these binaries play out in the relationship between Ishwar Singh and the corpse of the Muslim girl that he finds in the house he loots. These ideas later replay almost hauntingly between Kulwant Kaur and Ishwar Singh in the scene that is narrated to the readers. It is at the behest of this breakdown of meaning that we evoke the figure of the corpse: dejected and discarded. The corpse, at first glance, is the ultimate sign of the abject—not simply because it is a corpse, but because of what she was that resulted in her becoming a corpse: a young Muslim woman on the wrong side of the invisible border fence. Cold and desolate, the corpse is rejected by her people, her land, her language—and is picked off by Ishwar Singh, who, up until just a few days (or even hours) before this occurrence, was an insignificant subject of his colonial masters and had now himself become that same master. There, this beautiful and rather demure fainted girl (as it is in Ishwar Singh’s imagination) is taken to be the subject of his pleasure, detached from any meaning of her own—a de-subjectivized subject, a mere body.

The theme of the consumable colonial body remains persistent in the construction of this narrative and is represented through Ishwar Singh’s imagination of the Muslim girl, as portrayed by Manto through the usage of mawa chakhna in the original Urdu version and also in the English translation, where the rape of the girl is narrated by him as the “gorging of a luscious fruit.” Both of these versions point towards the act of eating and the consumption of what is believed to be owned. For the colonial master, the colonial subject’s body serves first and foremost the function of a commodity—a commodity that, much like under capitalism, must produce maximum benefit with the least amount of investment. The body of the colonial subject is purely an object that produces, whose self and production are both under the ownership of the master. The master’s body “was highly masculine and ableist. All 'other' bodies were considered as potential resources to meet the needs of the ableist body” (Menon, 2). For Ishwar Singh as well, the consumption of this ‘othered’ body is a signifier of possession and mastery over what he believes himself to have assumed power. The commodification of the girl’s body—meant to be consumed by Ishwar Singh—therefore brings to attention its object status: something that can be owned, sold, used, and stolen. This phenomenon is also noted by Fanon, who describes his own body as “an object in the midst of other objects” (82).

The girl is metaphorically already dead in Ishwar Singh’s imagination long before he finds out—in concrete terms—that she is dead: the perfect colonial body. It is then curious to see how the initial imagination doesn’t budge him in the slightest, but the knowledge that the girl is dead (which only confirms what he had already known and acted upon) destroys him completely. In this reading, it is somewhat clear what shifts so drastically between those two positions. What shifts is what Ishwar Singh perceives himself to have possessed—what he believed himself to be in this situation: a stand-in for the master. He is the possessor. There is something inherently subversive about the figure of this helpless, seemingly lifeless (and therefore submissive) girl lying at his mercy—only to turn around as the ultimate transgressor. This corpse brings to reality what has always been feared but, in that moment, not expected out of a demure figure like hers: castration. For Kristeva, the abject is “death infecting life,” that which “is something rejected from which one does not part, from which one does not protect oneself as from an object. Imaginary uncanniness and real threat, it beckons to us and ends up engulfing us” (4).

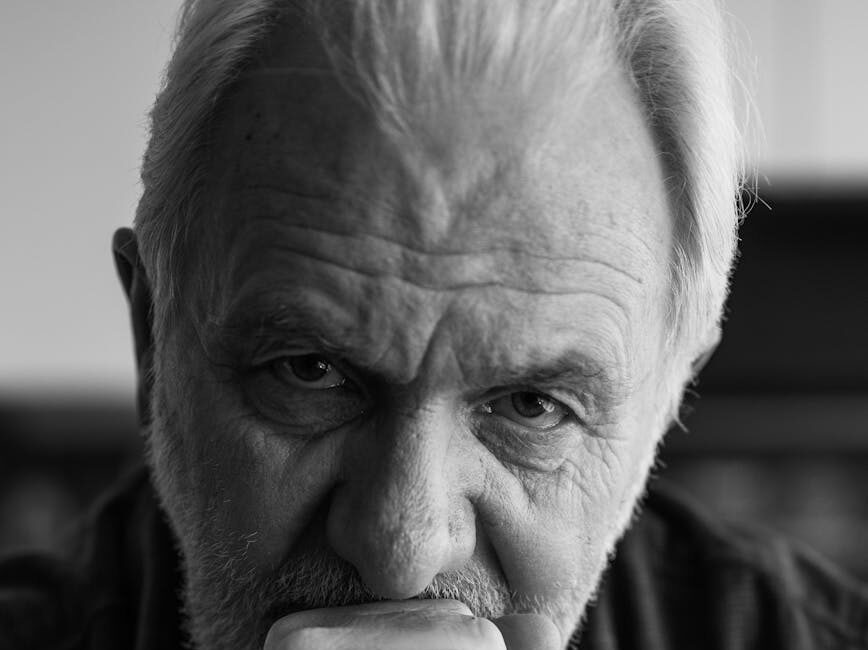

As we follow the figure of this corpse, which comes to Ishwar Singh as death personified, what has plagued him becomes more and more apparent. As he goes through the process of denial and tries everything to prove otherwise, the gaping sight of terror looks directly into the eyes of both him and the readers, who realize that it is not simply the cadaver that is abject—but that Ishwar Singh himself has turned into the abject—for the corpse of the young girl has robbed the man of the very essence of his life: his virility, his manhood. The true horror for Ishwar Singh, perhaps, is not simply the violation that he suffers but by whose hands that violation has occurred. Like a spectre, the memory haunts Ishwar Singh, lurking just beneath the surface of his being, ready to creep up and shatter everything. The seemingly hypermasculine figure of Ishwar Singh, reinforced by Manto through the description of his stature and compatibility with a woman like Kulwant Kaur, is undone by the lifeless corpse of a young girl. In the haze of my somewhat phantasmic reading of the story, I believe it is in the dead eyes of the corpse that Ishwar Singh sees himself—a mirror reflection of what he had become and what he had lost. The cadaver of this girl is, first and foremost, a double of Ishwar Singh: a double that reveals the outlines of his own being and, within the same fraction of a moment, the inescapable decay of the same. What Ishwar Singh had so eagerly tried to escape has now swallowed him whole—he too has been resigned to the same fate as the powerless and de-subjectivized colonial body.

As the lines between ‘I’ and ‘Other’ blur between Ishwar Singh and the corpse of the Muslim girl, I want to mention Mladen Dolar, who, while referring to the Lacanian mirror stage in connection with the Freudian uncanny, writes:

When I recognize myself in the mirror it is already too late. There is a split: I cannot recognize myself and at the same time be one with myself. With the recognition I have already lost what one could call "self-being," the immediate coincidence with myself in my being and jouissance. The rejoicing in the mirror image, the pleasure and the self-indulgence, has already been paid for. The mirror double immediately introduces the dimension of castration. (12)

In the reflection of the mirror that the corpse becomes for Ishwar Singh, he sees the disintegration of his own body—one that leaves him paralyzed, stuck in a spiral of inglorious bodily failure, which is more than just physical. It is the outline of his body and that of the corpse that begin to blur into oneness. The border between the victim and the monster begins to collapse—the monster sees himself in the victim, and the victim, in turn, becomes the monster. Under the shadow of the dread and horror that was colonialism and the Partition, each one involved asked the question: how did I become the monster? After all, the abject is abjected for a reason. As Kristeva writes:

A massive, and sudden emergence of uncanniness, which, familiar as it might have been in an opaque and forgotten life, now harries me as radically separate, loathsome. Not me. Not that. But not I—nothing, either. A "something" that I do not recognize as a thing. A weight of meaninglessness, about which there is nothing insignificant, and which crushes me. On the edge of non-existence and hallucination, of a reality that, if I acknowledge it, annihilates me. There, abject and abjection are my safeguards. The primers of my culture. (2)